VR’s Biggest Problem and How We Could (Maybe) Solve It

When people see themselves move somewhere in VR, while their inner ear doesn’t feel any movement, they can get motion sickness.

And this is a huge problem, because (1) over half the world’s population gets it in VR and (2) it doesn’t matter how good the gameplay or narrative or art is . . . if you feel like throwing up the entire time.

Yes, it’s true that you can get used to motion sickness and many VR players have.

But this can take several weeks or even months. So good luck asking most people to go through all of that discomfort just to play games that may or may not be good.

Why not just play Baldur’s Gate 3 instead? Or any of the thousand other great PC, console, or mobile games?

So, unless VR developers want to immediately lose half of their potential audience, they end up having to choose between:

Not having any movement

Or spending a lot of time designing a custom, restricted movement system that doesn’t cause motion sickness.

But why does this matter? Who cares about movement? Well, it just happens to be the most important action in all of videogames.

To see why it’s important, just watch someone playing any game with a character to control and see how often they aren’t moving around in some way.

It doesn’t matter if it’s Fortnite, Minecraft, League of Legends, World of Warcraft, Red Dead Redemption, Counter Strike, or Among Us, the player will be moving >90% of the time.

Because movement is so important, not being able to do proper movement translates to a huge amount of extra effort just to make up for what was lost.

Just imagine trying to make an FPS game without flanking, a MOBA without the ability to sidestep abilities, or an action-adventure game without running and jumping.

Yes, there’s always a solution. But coming up with new ideas and then getting them to work takes a lot of development time away from other important things, like progression and combat systems.

So, without proper movement, it ends up being practically impossible to create games with anywhere near the depth of a PC or console game. It’s why every VR game still feels shallow or “gimmicky”.

But our struggles with motion sickness don’t even end there. Because, even if we avoid movement entirely, motion sickness can still be triggered in all sorts of unpredictable ways: a UI element popping up in the wrong way, an enemy sword bouncing around in your peripheral vision, a small lag spike — you name it.

And it’s hard to spot and troubleshoot issues these issues, since motion sickness is a nightmare to test for:

Some people are much more sensitive to motion sickness than others

People’s sensitivity will vary from day-to-day and even hour-to-hour

People can adapt over time and become less sensitive, which is especially a problem when developers gradually lose their ability to test their own games for motion sickness

Subtle levels of motion sickness might not produce any symptoms until 30 or more minutes into a game, meaning that its very hard to quickly test for

And subtle levels can even produce seemingly random symptoms that the player won’t associate with motion sickness, like eye strain, headaches, headset discomfort, disorientation, etc. Something will just feel “off” and that feeling will then miraculously disappear if they play a game that doesn’t cause motion sickness.

So, when we have a brutal problem that’s hard to test for, we get the current state of VR: every single developer will waste months of development effort on just dealing with motion sickness.

It’s the reason why the only truly successful VR games have been the small subset that work well without movement (like Beat Saber) and games that are targeted towards young kids (like Gorilla Tag), since they’re much less susceptible to motion sickness.

So, if we sum up all of the above problems and consider that VR gaming is already a >$15 billion market, I don’t think it’s radical to propose that motion sickness is a billion dollar problem.

And that’s not even taking into account how much bigger the VR market could be if motion sickness wasn’t a thing and we’d be able to make games that live up to the sci-fi potential of the technology.

Ok, it’s clearly a problem. But what do we do about it?

Where Should We Focus?

If we want to get anywhere, we’ll need to constrain the problem first.

So remember that motion sickness was all about the mismatch between seeing yourself move with your eyes, but not feeling it with your inner ear.

This means there are three important systems that matter when it comes to motion sickness:

The visual motion processing system that takes in inputs from your eyes

The vestibular motion processing system that takes in inputs from your inner ears

And the system that compares outputs from the two and detects a mismatch

Now, while the latter two are very important for motion sickness, we don’t really have easy access to them as VR developers:

To access the vestibular system, we’d have to exert influence inside your inner ear. That’s not impossible to do and there are already pills and vibrating devices that can do that. But we’d have to convince players to buy hardware or pop some pills, which wouldn’t be easy.

And, to access the comparison system, we’d have to affect something deep inside the brain, likely the medial superior temporal cortex (MST). And that seems way harder to access than your inner ear, especially since we don’t even know much about that system yet.

So I think it’s best to focus on the visual motion processing system, since there’s already a screen on the player’s face and we won’t have to try and sell hardware to anyone. We already have free access to their eyes.

Our goal, then, is to trick that system into not seeing any movement when you’re moving around in VR, which should prevent the mismatch from occurring in the first place.

And we think that messing with this system should work, since we’re already doing that in VR — you’re not actually moving around in a 3D world, you’re just seeing pixels move on a 2D screen.

Plus, it’s also just very easy to fake movement with 2D optical illusions, so it would be strange if we couldn’t figure out ways to cheat the system in 3D as well.

That’s why I think it’s worth putting our eggs into this basket.

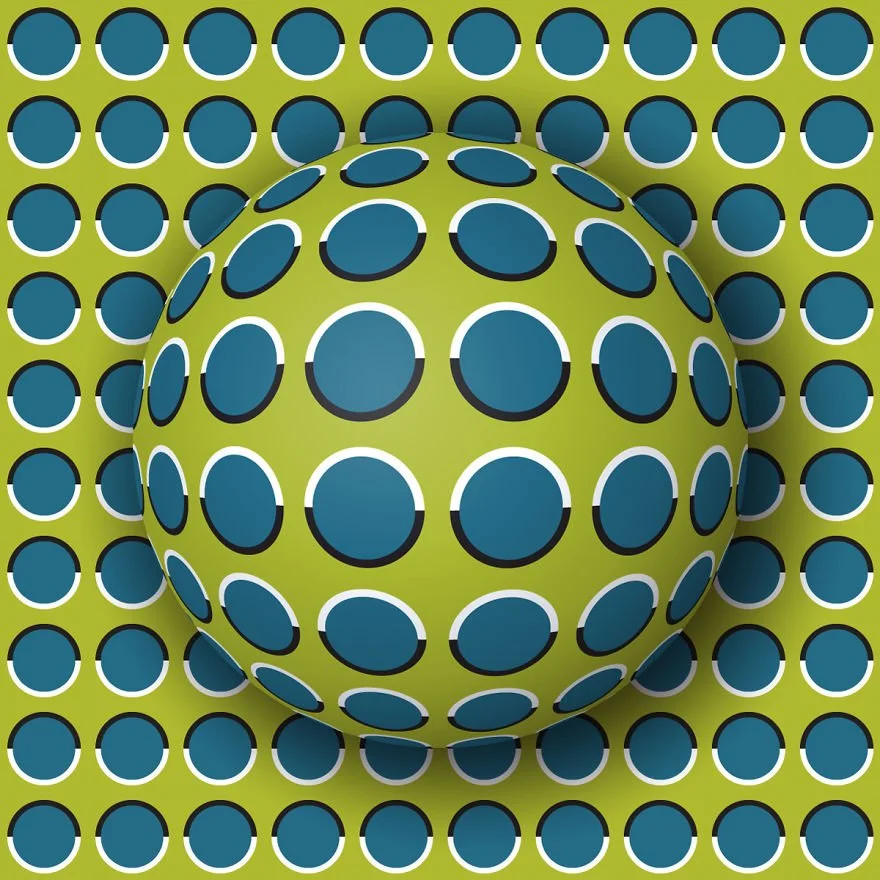

If you put your cursor above one of the dots, you’ll realize that nothing is actually moving in this illusion by Dr. Kitaoka.

Why Don’t Existing Visual Solutions Work?

But, before we talk about any new ideas, there must be solutions out there already, right? If motion sickness is such a big problem, people must have come up with ways to solve it.

And that’s true. It’s been one of the most studied areas of VR.

However, most of this research has been built around a critical assumption: when we see ourselves move, we see it just like anything else — through the full spectrum of color, brightness, detail, and whatever else.

So, because of this assumption, current techniques have understandably targeted that full spectrum.

For example, the most popular solution right now involves just completely blocking off everything in the player’s peripheral vision (called a vignette or field of view restrictor).

This way, players no longer see as much evidence of themselves moving. And less visual evidence of movement = less mismatch between your eyes and inner ear = less motion sickness.

An example of a VR vignette.

However, completely blocking off half the screen is incredibly distracting, hampers situational awareness during gameplay, and takes away the feeling of actually being in the world that’s supposed to justify putting on a clunky headset in the first place.

And, despite all this distraction, it still doesn’t prevent motion sickness well enough to let developers add proper movement to their games and applications.

Other popular techniques like blurring the periphery or turning smooth camera rotations into 45 degree jerks (called snap turning) suffer from similar problems. They sacrifice gameplay and visuals too much in exchange for too little motion sickness reduction.

And I suspect that the underlying reason why even disruptive techniques like these don’t work too well is that our motion processing system doesn’t actually see the world through the full spectrum of visual data.

In fact, according to decades of neuroscience research, it appears to mostly see:

Brightness contrasts, but not color contrasts (Edwards et al., 2021)

Big things, but not small details (Mikellidou et al., 2018)

Things in our peripheral vision, but not in our central vision (Luu et al., 2021)

And even things that we won’t consciously notice at all, like when we very subtly move everything on the screen at once (Levulis et al., 2025)

If these findings also apply to VR, then you can understand how existing techniques, which target things like color and detail, don’t work amazingly well.

By targeting everything we see, these techniques are doing a lot of collateral damage without truly getting rid of the things that do matter.

Visual Motion Processing

But why would our motion processing system see different information than the rest of our vision?

To answer this, let’s think about what our processing system is actually trying to achieve.

Simply put: it’s trying to determine motion in a very noisy environment with very little time and energy.

So, like any other biological system, it probably doesn’t use the full, raw data that reality provides us.

If it did, it would waste a lot of time and energy processing data that wasn’t useful.

For example, imagine running around a jungle full of small, swaying branches — a common scenario for our distant ancestors.

Then imagine how much processing the system would have to do if it seriously “considered” the movement of every single swaying branch.

And imagine how hard it would be to get an accurate movement direction for ourselves, if all that tiny movement wasn’t ignored or filtered away.

We’d very quickly get lost in the sea of noise, which would’ve completely prevented our ancestors from hunting prey and avoiding predators.

So, instead using every single piece of data that our retina takes in (which is already only a subset of reality), the motion processing system probably only uses what’s needed to reliably process motion.

Now what subset of data it does use is still not 100% clear, at least not to me. But here’s what I’ve found in the neuroscience literature so far:

The system only sees fast movement (high temporal frequency)

It won’t see things that are moving very slowly. We can intuitively experience this when animations stop feeling fluid when we go below around 10 frames per second. Movement below a certain speed doesn’t register as strongly.

But, it’ll also be able to spot very fast movement better than most other systems involved in vision. That’s why you’re able to recognize that something moved, even if you didn’t recognize, say, its form or color.

I ran some unofficial tests in VR and, yeah, very slow movement doesn’t really cause motion sickness. Neither does insanely fast movement or movement over a very short period of time.

Studies have found that around 10hz is the system’s preferred frequency (10 cycles of stripes per second as they pass by your visual field) (Mikellidou et al., 2018).

Above 30hz is where it seems to start dropping off hard (Derrington and Lennie, 1986). By comparison, most other components of your vision will stop being able to keep up above 20 hz (Skottun, 2013; Pawar et al., 2019; Chow et al., 2021; Edwards et al., 2021).

For some evidence of how this affects VR: a study on driving in VR found that driving at 120 mph caused around 1.4x more motion sicknes than at 60 mph (Hughes et al., 2024).

It only sees big things (low spatial frequency)

It won’t see small details, since small details that move are noisy/blurry and likely not as important as bigger objects. Specifically, the magnocellular pathway will stop responding to things above the 1.5 cycles per degree (cpd) (Skottun and Skoyles, 2010; Edwards et al., 2021). That’s about the size of a small tree that’s 10 meters away.

My unofficial tests in VR showed that the stripes that caused the most motion sickness were indeed around the 1-1.5 cpd range. Stripes smaller than that didn’t do much.

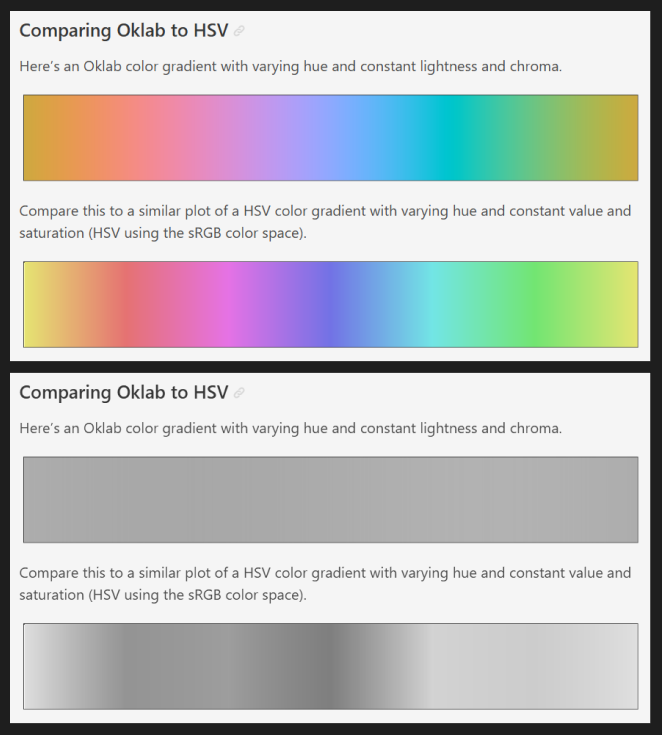

An approximation of what the motion processing system would see if it had 1.5 cpd vision.

An approximation of what the motion processing system would see if it filtered for <1.5 cpd spatial frequency instead (Edwards et al., 2021)

It mostly sees brightness (luminance contrast)

It (mostly) doesn’t see color, which we can experience when some object moves by us super fast and that object will just appear as a shadow.

Color is still somewhat involved in motion processing, especially when there isn’t any brightness data available. But it’s not nearly as important (Derrington, 2000; Aleci and Belcastro, 2016; Edwards et al., 2021).

The system can apparently see brightness contrasts as low as 0.5% (Aleci and Belcastro, 2016) and responds clearly to contrasts of around 4-8% (Butler et al., 2007).

The primary importance of brightness and low spatial frequency information are supported by “motion standstill” illusions (see video below). These are cases where high spatial frequency dots with high brightness contrast can completely hide the motion of shapes, if these shapes have smooth edges and no brightness contrast (Dürsteler, 2014).

My own unofficial experiments showed that, in scenes with nothing other than brightness contrast, there was a pretty substantial drop-off in motion sickness when we went below 20% brightness contrast (in whatever units Unity uses) and an even bigger one below around 5%. Motion sickness also didn’t get much worse going from 40% to 100%.

But keep in mind that the system isn’t tricked by global brightness changes, like what happens when the sun pops up from behind the clouds.

This is because the system has brain cells that look for brightness changes in a particular direction, as well as cells that look for brightness changes in all directions. If the latter cells spot a brightness change in all directions, they cancel out the signal from the directional cells and there’s no perception of movement (Im and Fried, 2016).

The orange spiral is actually moving, as you’ll see if you place your cursor on its edge. It’s less effective here (because of frame rate/color differences), so check out the original video by Max Reinhard Dürsteler.

What it sees depends on speed, spatial frequency, and temporal frequency

It sees fast motion at low spatial frequencies just as well as slow motion at high spatial frequencies (Mikellidou et al., 2018)

More reading: Wichmann and Henning, 1998, O’Carroll and Wiederman, 2014

Contrast sensitivity = how easily people can tell that something is moving (Mikellidou et al., 2018)

It’s more sure of what it sees if there are lots of edges in different orientations that move together

Intuitively, there’s a pretty low chance of a bunch of random stuff all moving together in the same way, unless you’re the one moving. So the system seems to rely on a lot of stuff in different orientations moving together in a correlated way (Diels and Howarth, 2009; Palmisano et al., 2015).

Not directly related, but it probably feels much worse to move diagonally than forward in VR because you’re seeing things move along both the z- and x-axis, rather than just one. That’s double the visual information and therefore double (or more) of a mismatch with what your inner ear is feeling.

Isotropic noise should theoretically be the most effective at causing motion sickness, since it’s noise “in all orientations” and therefore makes for the most reliable signal. Image from 3Delight Cloud

It sees things in peripheral vision

It’s much better at responding to stuff that’s happening in your peripheral vision than other systems involved in vision (Baseler and Sutter, 1997).

You can experience this by testing how hard it is to see an object far in your peripheral vision when it’s not moving versus when it is. Moving objects are much more noticeable in peripheral vision, since this system is taking care of that.

An interesting example of this is that people with vision loss in their central vision appear to feel more motion sickness than people with normal vision. And people with vision loss in their peripheral vision seem to feel less of it (Luu et al., 2021).

Interestingly, it seems like there are scenarios where we’ll perceive the direction of motion differently depending on whether it happens in our central or peripheral vision (Allard and Faubert, 2016). I recommend checking out video 5 of their supplemental data for the best example. The authors argue that this is due to our peripheral vision having less accuracy when it comes to determining position.

It gets used to things after they move at a constant speed for a while

Basically, it’ll stop responding as strongly to the constant movement after a while. When it does that, it’ll instead start looking for smaller relative speed differences between objects in a scene (Clifford and Wenderoth, 1999).

This is probably because relaying the same “you’re going this fast” information over and over again isn’t particularly useful, so it’s mostly communicating important changes (i.e., accelerations).

One study found that this adaptation started to happen after 3 seconds at the neuron level (Wezel and Britten, 2002). My (non-rigorous) tests found that it started to happen around 4-10 seconds of being at the same constant speed in VR.

This effect is why games where you constantly run forward, like Pistol Whip, don’t cause much motion sickness.

Full Flight simulators already exploit something similar. Basically, simulators can’t actually mirror the real rotation of the simulated flight, since they can’t rotate the full 360 degrees and since there’s no actual forward motion to counteract gravity (like there is while flying). To solve this, they use a washout filter, where the simulator is returned to level after a rotation, but this is done so gradually that our vestibular system doesn’t detect it (Micomonaco, 2019).

It sees nothing during eye movements and is most sensitive right after them

Our eyes do small, subconscious movements multiple times a second to correct for drift. Plus, they’ll also do bigger movements as we focus on new things in our environment. These eye movements are called saccades.

To prevent us from confusing our saccades with actual movements in the scene, our motion processing turns off during that small period of time (Binda and Morrone, 2018).

There’s also a moment right after a saccade where the system tries to catch up to what it missed and is extra sensitive to motion (Frost and Niemeier, 2016).

The system also obviously turns off when you’re blinking. So, if we do eye tracking to track blinks and saccades, we can use those moments to hide all sorts of stuff.

One well-known technique shifts the entire scene around during these moments, so that you can do what seems like walking forward, but actually be walking around in a circle perpetually (Sun et al., 2018). Although, it still requires a lot of space and doesn’t allow for anything faster than very slow walking.

It is, at least in part, a subconscious process that’s distinct from the rest of our vision

A study by Levulis et al. (2025) found that even imperceptible levels of camera jitter caused motion sickness in a VR game.

I’ve also managed to accidentally cause very serious motion sickness with camera movements (or screenshake) so small that you couldn’t tell anything was happening. Some frequencies were especially nauseating, but I never recorded what they were (I plan on returning to this later).

A few studies have also shown that we can also experience motion after effects when exposed to motion we don’t consciously perceive (Lee and Lu, 2014; Roumani and Moutoussis, 2020).

It also seems like imperceptibly fast flickering can also affect spatial processing (Jovanovic et al., 2025). Considering that spatial processing uses the same magnocellular pathway, I’d say a decent chance imperceptible flicker can also affect motion processing.

One study also showed that motion perception can be impacted by a stimulus that occurs for just 25ms (Glasser et al., 2011). That’s about 2 frames in a 72 fps VR game. Based on prior experience, I suspect a change that fast might still be barely noticeable, but maybe not if you’re paying attention to something else.

It might even be possible to notice motion despite otherwise being blind (if this is the result of damage to brain regions that are responsible for vision, but not motion processing). This is called Riddoch syndrome.

All of the above findings are very important because it means we might be able to attack motion processing in a completely imperceptible way.

It seems to care more about things happening in the perceptual background

If the motion occurs in what we perceive to be the foreground against a stationary background, it might cause less motion sickness (Nakamura, 2006).

The system probably does this separation because we don’t want to falsely think we’re moving if it’s just some objects in the foreground moving. By comparison, it’s unlikely that everything in the background moves unless we’re the ones moving.

The background is probably determined with a combination of depth and motion cues, like background objects being blocked by foreground objects (occlusion) or background objects being far in the distance and therefore all moving at slower speed than things in the foreground (motion parallax).

However, I have no idea to what extent our motion processing actually uses depth cues. Intuitively, I’d expect it to only use the few depth cues that are necessary for reliable motion processing, but that’s not saying much.

And here are some other things we found:

Depth and form information might be used more when other inputs are otherwise ambigious. We can theoretically determine motion purely from depth or form, through the cues like the ones I just mentioned (objects increasing/decreasing in size as we get closer/further away from them).

However, these mostly seem to be used when we can’t use simpler cues instead (Kim et al., 2022). I suspect that this is because these depth and form cues aren’t super accurate and/or because they might involve costlier, higher-order processing, so it’s best to use them only when needed.

Horizons seem to provide important, stable reference points. Namely, at least one study has shown that having a stable horizon line reduces motion sickness (Hemmerich et al., 2020). I’m not sure if this is because the system is explicity tracking a horizon using things like vanishing points or if the horizon is just treated as an obvious brightness contrast on a very large background object. Interestingly, my testing showed that adding more stationary reference points paradoxically caused more motion sickness if they broke up the horizon line.

The system seems very good at dealing with visual noise. As many of the above papers have found, noise of roughly a 1 cpd spatial resolution felt the most disorienting in my brief tests. But no amount of noise seemed to significantly prevent motion sickness. I only tried noise on a two dimensional layer, though. So maybe three dimensional noise with actual depth would work better, since our motion processing system may simply discount the noise as irrelevant foreground movement.

Some noise even seems to increase the reliability of visual motion cues (Palmisano et al., 2000). One explanation is that our heads are subtly moving around constantly, which creates very subtle motion parallax cues that might help us perceive movement in depth (Fulvio et al., 2021).

Having no brightness contrast at all might make motion sickness worse, because they’re so important for orienting ourselves in a scene (Bonato et al., 2004). Personally couldn’t replicate this, it just made things less intense for me.

It might be turned off if there’s diffuse red background and rapid flickering (Lee et al., 1989; Hugrass et al., 2018; Edwards et al., 2021). Couldn’t replicate this.

It might struggle when there are lots of objects right next to each other (Millin et al., 2013; Atilgan et al., 2020). Also couldn’t replicate this.

It should shift to relying purely on low spatial frequency luminance contrasts when the scene is dark. This is because cones (that provide color input) don’t work in low-light conditions (Zele and Cao, 2015). It’s why colors become less saturated when you’re walking around in darkness.

It might discount movement when we expect it to happen or, conversely, enhance movement that we don’t expect to happen. There are some studies that found motion sickness to be worse when it was unexpected (Kuiper et al., 2019; Teixeira et al., 2022). I haven’t tested it myself, but many of the VR developers I’ve talked to have mentioned this as a major factor. One logical explanation is that our brains are primed to notice unexpected changes to ensure that we respond quickly. So unexpected signals may have higher weights in motion processing too.

It seems to discount movement if you move your body, perhaps even in ways that don’t really match the movement. For example, just moving your hands around during any movement seems to help prevent motion sickness. This could be because moving your hands with any kind of force also causes your head to move, which means less mismatch between your inner ear and what you see. But it might also be that your moving hands keep “telling” your brain to ignore them, through something called efference copies. Otherwise, if your hands passed right by your face, your brain might mistakenly think you moved somewhere (since your whole view is moving in that situation). And those “ignore me” messages might not be perfectly specific, so any big body movements might cause you to ignore some random motion cues. But that’s just a wild theory.

The system seems to struggle when there are harsh changes between several contrast levels, especially on small objects in our peripheral vision. For example, smooth luminance transitions aren’t as problematic as step changes and long edges aren’t as problematic as fragmented or curved edges (Kitaoka, 2003). It likely has something to do with how motion processing in our peripheral vision is updated after a saccade, given that some motion illusions trigger whenever you look somewhere else and stop working if you make the image small enough (see Dr. Kitaoka’s illusions or these illusions by Michael Bach).

The system also generally gets fooled by pure contrast changes, even if no movement actually happens. The illusion gif at the start of this write-up was one example, but here are some more detailed explanations of how these “reverse phi” illusions work: Kitaoka, 2014; Rogers et al., 2019; Bach et al., 2020. And I’d also recommend looking into Luo et al. (2020) explanation of the “serpentine illusion”.

There are also mathematical and machine learning models of motion processing, which could open up more avenues of attack (Adelson and Bergen, 1984; Simoncelli and Heeger, 1998; Mather, 2013; Soto et al., 2020; Eskikand et al., 2023; Clark and Fitzgerald, 2024; Su, 2025). The most promising one seems to be the one by Sun et al. (2025), since it even replicates human failure cases like the reverse phi illusion.

Illusory motion is used to enhance depth in this image by Yurii Perepadia (2018).

How to Trick the System

Ok, so we have a motion processing system that only responds to the most important image features for that task. These are called motion cues.

And, critically, these cues are different from those used in other sub-systems within human vision, especially those responsible for our central vision.

Why is that? Well, because our motion processing system isn’t uniquely efficient. Every other visual processing task will also only process what it needs.

So, as long as two tasks differ to the extent that the same data can’t be efficiently reused, the input data (or cues) should be different between them. Or so my initial intuitions go.

And the processing tasks that constitute our central vision are quite different from those required to see ourselves move, so we should expect the relevant cues to be quite different too.

This means, at least theoretically, we should be able to selectively target only motion cues and therefore prevent motion sickness without significant visual disruption — at least to the extent that motion cues are distinct from other visual cues.

But how much do we have to do? How many motion cues do we have to remove to no longer have a mismatch between our eyes and inner ears?

Long story short, I don’t know the answer. What the literature does say, though, is that the comparison between eyes and inner ears seems to roughly work via reliability-weighted summation (Fetsch et al., 2011; ter Horst et al., 2015).

What that means is that data streams coming in from the eye and inner ear are given higher weights if they’re deemed more reliable. In other words, the more reliable signal is the one that will be trusted more for determining whether we’re actually moving.

And reliability very roughly seems to be measured by how many neurons that look at the same thing fire at the same time. Because, intuitively, it’s pretty unlikely that random noise would cause only every relevant neuron to fire at the same time.

So, to reduce motion sickness, we must reduce the reliability of visual motion cues that imply we’re moving, in a minimally perceptible way.

We want to get our brain to trust our inner ear instead (or any visual motion cues that do align with our real-world movements).

And that leads us to two general options:

Remove (or otherwise reduce the reliability of) motion cues from the moving environment, in a way that minimally affects the rest of our vision

Add reliable motion cues from another environment that isn’t moving (like our real-life room), in a way that minimally affects the rest of our vision

Now, the importance of the first option is obvious, but why would we have to do the second one?

The reason is that it’ll probably get harder and harder to remove the last little motion cues from the screen. Our brains may instead start placing more trust on the few remaining cues, which would oppose our progress.

So, to truly prevent all sensation of motion, we might have to use stronger and stronger removal techniques, which will cause more visual disruption.

But, if we instead bring in cues from a stationary environment, those might help counteract the motion cues we’re seeing on the screen. And that would let us get away with less removing and therefore less visual disruption.

But what does removing and adding motion cues actually look like?

Well, here’s a simple example: we already know that motion processing is mostly about (a) brightness contrast in (b) our peripheral vision.

So, to reduce motion sickness, we could remove (a) brightness contrast in (b) our peripheral vision.

We wouldn’t touch color or detail or anything in our central vision. Objects in your peripheral vision would just all be at the same brightness level, which isn’t very noticeable.

Then we could add (a) brightness contrasts to (b) our peripheral vision from a stationary environment instead. That way, we’d get the motion cues we’d expect if we were just chilling in our rooms.

The point is that this selective addition and removal of motion cues would theoretically reduce motion sickness in a way that isn’t very perceptible.

From top to bottom: a color gradient with all brightness differences removed > a normal gradient > greyscale version of gradient with no brightness differences > greyscale version of normal gradient. Note how we just removed brightness without touching color. Image source: Ottoson, 2020

The Manual Approach

Now one way to do all of the above is a manual approach. Here’s a rough idea of how that might work:

Do further research into what exactly counts as a motion cue

Figure out which motion cues are most important in 3D (on a VR screen)

Go through each cue and figure out ways to add or remove it, until there’s no more motion sickness (within, say, a 2 hour game session for 90% of players)

And then come up with ways to do so less perceptibly, just like researchers have already done for techniques like redirected walking algorithms in VR and washout filters in flight simulators. In our case, that could mean something like making our cues flicker so fast or keeping their movement so small that they can only be processed subconsciously.

Basically, this will take a lot of trial and error. And that’s exactly what I’ve been doing, since it’s the easiest thing to start with.

Here are some of the techniques I’ve tested so far:

Grid noise

I’ve tried splitting up the image into a grid and adding random rotations and displacements at random frequencies to the images on the grid.

The goal with this techniques is to try and reduce the reliability of all motion cues.

But it seems like the motion processing system is very, very resistant to noise. And any noise that isn’t perfectly incoherent/random in all directions seems to just make motion sickness worse, since it’ll just provide more motion cues in some direction.

However, I didn’t put much effort into testing this. So there are almost certainly better ways to generate incoherent 3D noise to reduce the reliability of motion cues.

Grid flicker

This involves, again, splitting the screen into a grid. But instead of messing with rotations and displacements, I’m instead just randomly changing the brightness of each square.

This does reduce motion sickness a bit (in my very non-rigorous testing). And, surprisingly, lower flicker rates and lower flicker intensities also seem to work better than high ones.

I don’t know why this is the case, but I suspect it might have something to do with how this less intense flicker can make it seem like there’s an unmoving wall right in front of you.

So it might provide a stable reference point that conflicts with motion cues. But more study is needed on this one.

An example of grid flicker.

Counteracting blobs

This technique just involves spawning a blob of brightness that moves either exactly opposite or orthogonally relative to objects in the scene.

Just like with grid noise, the limitation of this technique seems to be that you need to get the brightness, speed, and size of the blob within the right range to counteract the exact motion.

It also seems way less effective in 3D than in prior 2D experiments, probably because we can shift to relying on depth cues instead. But, again, my tests were only preliminary.

Reverse phi illusion

This is an illusion that tricks us into seeing movement with just contrast changes alone.

We can replicate it by having an image with two or more frames, where each frame shifts the image slightly and features swap from black to white (easier to see through Dr. Kitaoka’s 2D examples).

I tried using this to counteract moving objects in a simple scene with no other elements. It worked, but it was disorienting and very distracting.

I still need to test this in a more complicated scene with lower contrast levels.

Brightness vignette

For this, we’ll just remove all brightness contrast from the player’s peripheral vision. This is done by first converting RGB into a perceptual color space (Oklab), setting perceptual brightness (lightness) to the same value, and then converting back to RGB.

We have to do this conversion because the brightness value of RGB colors doesn’t match how we actually perceive brightness, so setting everything to the same value would still lead to noticeable brightness differences.

So far, it’s been about half as effective as completely blocking the player’s peripheral vision (again, this is just an initial result from some crappy testing).

This is probably because color and other cues are still somewhat used in motion processing and they’re probably relied upon more when there’s no brightness data available.

But, on the plus side, the technique is barely noticeable and nonetheless better than nothing.

I suspect that it’ll also work much better if combined with a technique that adds motion cues from a stationary environment, since it might make our motion processing system rely on those cues instead.

An example of a brightness vignette we made, where brightness contrast is removed from the periphery (it’s pretty subtle).

Peripheral slowing

The idea is to slow down movement on the periphery, since stuff moving faster as it gets closer to us is a key depth cue and motion processing mostly relies on our peripheral vision.

When I tried it, it kind of worked. But making the effect strong would create this reflexive lean forward response, probably to maintain balance during what we perceive as a sudden change in speed.

Thankfully, there’s already existing research on a much smarter version of this and they’ve done a way better job testing it (Groth et al., 2024).

High-pass filtering

The idea is to filter away all low frequency visual information, which is likely what motion processing relies on.

I haven’t tested it yet because it’s likely very visually disruptive, unless we only target low frequency luminance information.

But it would be useful to see how important low frequency information is relative to other motion cues.

Left = applying a high-pass filter to remove low frequency information. Right = if we now apply a blur that represents how your motion processing system (probably) sees things, it no longer sees anything from the filtered image.

Edge noise

The idea is to add noise to object edges, since edge detection is one of the earliest steps of motion processing and that might mess things up.

I haven’t tested this yet.

Low spatial frequency noise

Another noise technique, but this time just random (very large) brightness blobs moving past the screen.

This seems to do something, but it runs into the same problem where it’s hard to make the noise truly incoherent and not just make motion sickness worse.

Artificial horizon

This isn’t a new idea at all, but I wanted to test it anyways. Here I just split the screen into two halves and made one brighter than the other, such that an artificial horizon was created.

This works very well, even when no effort is put into making it realistic. It seems especially effective at mitigating motion sickness from camera rotations (which would otherwise cause huge amounts of motion sickness).

Stationary reference points

The idea is to explore various ways of rendering motion cues from a stationary scene on top of the screen (like translucent walls/grids/blobs).

Haven’t done much testing yet. But I did discover something interesting: bigger walls that are further away seem to be more effective as reference points than closer walls, despite providing less motion information on paper.

Walls being too close also just makes motion sickness worse, perhaps because subtle latency is much more noticeable on closer objects or because we reflexively fixate on large nearby objects.

The Automated Approach

Now the above manual approach will probably discover something interesting, since we’re at least being guided by neuroscience and not just pure trial and error.

But we’re still talking about attacking a system that’s been optimized over 80 million years to be very resistant to noise — for our ancestors, slightly miscalculating the motion of a branch while swinging around in a jungle would’ve pretty much led to instant death.

So, while there’s no doubt the system is fallible (as proven by the existence of motion illusions), it might nonetheless require a magical combination of lots of different parameters that might even need to be adjusted in real-time.

So, while discovering this magic combo would probably make us feel very smart and accomplished, it might be worth outsourcing that trial and error to a machine learning model instead. They’re just much better at tuning a bunch of parameters than we are.

So the general idea would be to:

Use motion sickness data to train a model that predicts motion sickness using only raw video footage from games and other simulated environments (a motion sickness discriminator)

Then train another model to attack that motion sickness model by generating anti-motion noise (a motion noise generator). The idea being that this noise would target just the right parameters to stop our motion processing system from “seeing” us moving.

And to prevent this noise from being too distracting, we could limit how much that model could actually change the image we see and/or use another existing image quality model to punish overly disruptive noise (a visual artefact discriminator).

This idea didn’t come from nowhere. From my understanding, it’s the rough method by which machine learning researchers get image recognition networks to see, say, a cat instead of a dog, despite no perceptible differences in the image (the field is called adversarial machine learning).

But there’s a problem. To train a motion sickness model, we’ll need a lot of accurately-labelled video footage of scenarios that cause various degrees of motion sickness.

And getting that data is a huge pain. Like I mentioned before, data collection is complicated by person-to-person variance, day-to-day variance, people getting used to motion sickness over time, and symptoms only stacking up over long periods of time.

So we have a few options:

Using existing data

First off, we could try to use existing datasets, like this one by Wen et al. (2023).

But the problem is those researchers also had to deal with the same data collection issues as everyone else. So I suspect there still isn’t enough data and the accuracy of motion sickness labels on that data might not be high enough.

This is especially the case since the footage is often recorded at 30fps. That assumption automatically means that the model wouldn’t be able to learn how to imperceptibly “show” things to our motion processing system through the two likeliest methods (in my opinion): very fast flicker and very small movements.

But it might still be worth trying.

Getting our own data

The next option, then, is to get our own data. But we’d run into the same issues as everyone else.

So we’d likely have to work with a hardware provider directly, since they’re the only entity with both the incentive and resources to run a huge data collection effort.

Sounds great, but hardware providers won’t shift their R&D budgets to work with random researchers and, more importantly, every big hardware player is moving away from VR to the promised land of AR (with its billion-user potential).

For context, AR has different use cases and motion sickness isn’t as big of a problem in AR as it is in VR. So motion sickness isn’t a priority for the likes of Meta, which is the real reason why nobody has solved the problem.

Regardless, here’s a general plan of how we might collect that data:

Figure out some way to easily tell if the user is getting motion sick. We might, for example, add new sensors to track proven motion sickness proxies (like heart rate variability), add a “panic button” that players can press the moment they start feeling motion sickness (to escape into a re-orienting scene and give us data by doing so), and/or add a simple “did you get motion sickness?” question the first time a new player quits a game.

Then have headset manufacturers continually record video of what the player sees in a game and then save, say, the 10 seconds of footage prior to motion sickness.

But if we can’t get data from a headset manufacturer, we might still be able to record our own game footage and simply label each clip according to whether the game as a whole causes motion sickness for most players.

An ok approximation for this is the comfort label found on the Meta store. They seem to match reality in most cases.

Of course, labelling clips like this would make for some very noisy data, but there’s a small chance it might be good enough.

Then, regardless of how we get the motion sickness label, we’ll also have to attach further data on controller and headset positions to make sure the model learns which types of visual-vestibular mismatch unexpectedly don’t cause problems.

These surprising edge cases do exist, because I already know a few of them.

One example is the screenshake in Until You Fall, which doesn’t seem to cause motion sickness for most people.

And that’s miraculous, because screenshake is usually deadly in VR — as I mentioned earlier, I’ve managed to cause motion sickness with just a few millimeters of screenshake. So there’s some kind of voodoo magic behind Until You Fall’s implementation.

Another example is finishers in Batman: Arkham Shadow. These finishers move the camera around a lot, but miraculously don’t cause much motion sickness. Having talked to some of the developers, I know they don’t really know why themselves. It was just the result of testing every possible camera movement.

Nonetheless, even with high quality labels and controller data, we still might not get a good enough signal for training a model.

That’s because, as mentioned earlier, subtle levels of motion sickness usually aren’t noticeable until it stacks up for tens of minutes, after which it’ll quickly become overwhelming.

This delay between motion sickness onset will probably cause a lot of noise, since a large portion of footage that isn’t labelled for motion sickness will actually cause it eventually.

That being said, other fields have faced similar problems and have some techniques to deal with it, so it’s probably solvable with enough effort.

Using an existing motion sickness model

But, as it turns out, we might get to be super lazy and just attack an existing model of motion sickness.

This one by Zhu et al. (2025) seems like a decent target, since it at least only uses video footage.

For context, most other motion sickness models also use things like heart rate or head position, which means that we wouldn’t be able to attack them by only adding visual noise to a video.

But there’s a decent chance that these existing models aren’t good enough for finding a signal, since, again, everyone suffers from poor quality data.

Using an existing motion processing model

Lastly, we can attack an existing motion processing model, as opposed to a motion sickness model.

In other words, there are models out there that try to predict which way a human thinks an object is moving, even in complex scenes.

This one by Sun et al. (2025) seems the most promising, since it even predicts common failure cases of human motion processing (like the reverse phi illusion).

The reason why these models are interesting is that they’re trained on much, much better data. It’s just a lot easier to get data on which way humans think an object is moving in 2D than to get data on motion sickness in 3D.

So I suspect they’ll better reflect human motion processing and therefore make it likelier that any attack on them also works on humans.

The problem, though, is that motion processing in 2D obviously isn’t the same as motion processing in 3D. And, moreover, object-motion processing isn’t the same as self-motion processing.

But I suspect we’ll still learn something interesting about our motion processing system and, most importantly, this approach isn’t too costly to try.

What to Do?

So which approach should we go with? I think existing motion sickness models probably don’t mirror human motion processing well enough that attacking them would produce something that applies to humans too. And, as mentioned before, there probably isn’t enough data out there to make a better one.

BUT these are all assumptions that might well be proven wrong.

Nonetheless, I still think attacking a model is probably a better option than trying to beat 80 million years of evolution through trial-and-error.

Mostly because I’m lazy, but also because I suspect even a failure would be profoundly interesting and teach us a lot more about the problem.

Since motion processing models seem to be trained with better data, I’d probably attack those first, even if that attack won’t transfer over to a 3D scene in VR.

It’d be relatively quick to do and provide some degree of evidence for whether a general adversarial machine learning approach is possible with standard methods.

While doing that, we could keep coming up with and quickly testing manual approaches, since that’s pretty easy to do.

But hey those are just my quick thoughts. I’m open to alternatives, as long as someone finally solves this problem.